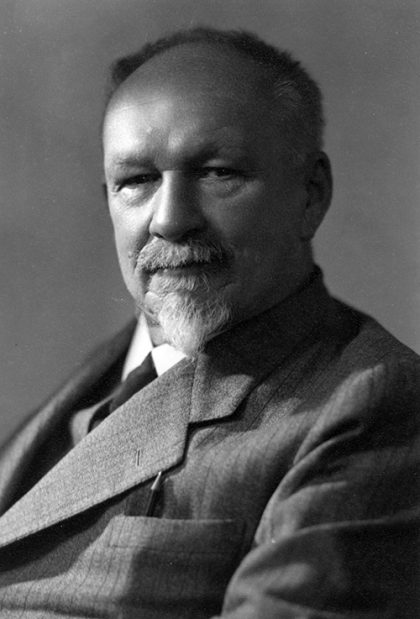

Jakob Künzler (1871–1949)

Humanist, missionary, and “Father of the Armenians”

“No herb, no bandage, no money, no care can heal the damage here either, but only the word of the Gospel, which heals all.” Berichte aus Urfa, 1906

Born under meager conditions as the second of seven children in Hundwil, Appenzell, Switzerland, Jakob Künzler had to take responsibility for his siblings early on, following the death of his father, as his mother also took ill and eventually died as well. Initially a carpenter by profession, he joined the Basel Diakoniehaus in 1893 and trained to become a Protestant nursing deacon, to be known as Brother Jakob. Künzler inherited a broad knowledge of the Bible from his grandmother, his confirmation pastor, and from the Pietistic brotherhood of Basel deacons, and in particular a strong belief in the illuminating, comforting, and forward-looking power of scripture.

Künzler, even after experiencing many strokes of fate, never lost his optimism. His understanding of faith pushed him to put it into action. In 1899, he joined the service of the German Orient Mission in southeastern Turkey, carrying in his luggage a revolver and a saddle. The young nurse joined the ranks of the mission hospital in Urfa, which treated people of all ethnic groups and religions. Cheerful and diplomatic, Künzler quickly learned the local languages: Arabic, Kurdish, Turkish, and Armenian. He made many friends, spent nights in Arab mud huts, and sang his Swiss songs to the people. He sought to break down prejudices between Christians and Muslims and bridge the divides between the religions through his work.

In 1895, the area had become the scene of a major massacre of Armenians, and the people’s hatred of the minority grew again during the First World War. During the systematic genocide between 1915 and 1917, which involved deportations, death marches, and mass murder, Künzler cared for patients unabatedly, continued to run the hospital as well he could, and, together with his wife Elisabeth Künzler-Bender, hid a large number of Armenians who would otherwise have been threatened with deportation, torture, and death. He was subsequently sentenced to death as a traitor to the country. The sentence was however never carried out. When a great famine broke out among the Kurds, he helped them as well. Künzler saw hundreds of corpses strewn all along the paths taken by the deportation trains. This strengthened his calling to always lend his support to victims. His wife had good connections within Muslim harems and, with the help of her friends there, was able to bring children and women to safety in Aleppo.

By 1922, nearly the entire Christian minority had fallen victim to the massacres. Künzler decided to close the clinic in Urfa and left for Lebanon with his family and 8,000 Armenian orphans on foot, in horse-drawn carriages, and in trucks. He subsequently looked after a large children’s home in Ghazir, which was financed by Near East Relief. There, over 1000 orphan girls were able to complete their apprenticeships as carpet weavers, and other schools and workshops would follow. From 1932 the Künzlers, supported by the Bund Schweizer Armenierfreunde (“Union of Swiss Friends of the Armenians”), built a settlement for 20,000 Armenian refugees near Beirut. A home for seniors, a home for the handicapped and a sanatorium followed as well. Künzler was given the honorary title “Father of the Armenians”.

The suffering of the persecuted Armenians would remain with him for the rest of his life. He presented their situation in Switzerland in many publications and lectures and collected donations in the country, as well as in the United States, where he referred to himself as a “professional beggar” upon his entry to the country.

Künzler’s book In the land of blood and tears is one of the most important contemporary publications documenting the mass murder of the Armenians. It captures the horror but also bears witness to people dedicated to providing help. His reports reflect a sense of reality and a trust in God that makes it possible not to despair, while also not downplaying anything. As he wrote: “It has always been a Christian’s duty to serve, indeed to love, those of other faiths. And I am convinced: In the end, it is not the mightiest sermon that will win the battle, but the greater love.”